Originally published on Boston Schools Fund Medium.

Without a long-term plan for fiscal certainty, BPS is headed for a fiscal cliff — with no Soft Landing for itself

This is part three of our five-part series on the BPS FY22 Budget Proposal. Read parts one and two.

The art of building budgets is no easy work, whether it’s for a city of 692,600 people, a district of 121 schools, or even for one’s own personal finances. Any change in circumstance — no matter how small — necessitates shifts between budget lines, a constant balancing act of money in versus money out.

And every budgetary shift represents a choice of how to respond to those changing circumstances. As President Joseph Biden said while still a Delaware Senator in 2008: “Don’t tell me what you value. Show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.”

A budget is just as much a statement of values as it is an outline of choices and how they are prioritized.

School budget season continues. On February 11, 2021, Boston Public Schools (BPS) CFO Nathan Kuder walked the School Committee through individual school budgets at its second FY22 budget hearing. With remarks from a handful of students and school principals, BPS presented the public with “faces behind the numbers” — and perhaps more strategically, their stories articulating critical budgetary needs made all the more urgent during the pandemic.

Our primary goal for our Budget Analysis series has been to clarify the complexities of the BPS budget by providing context and meaning to otherwise obtuse numbers. As we teased in our last post, this installment takes a deep dive into Weighted Student Funding, Soft Landings, and the fiscal implications of enrollment decline beyond just the FY22 budget.

The Art of Building School Budgets

In its simplest form, how BPS builds budgets for its schools is fairly straightforward: funding follows students.

Individual schools receive a certain amount of money for each student they enroll. But not all costs are equal, and students who have higher needs require more resources. BPS accounts for this using a Weighted Student Funding (WSF) formula, in which a variety of higher student needs are taken into account.

Using a very detailed WSF table, BPS assigns different monetary amounts, or weights, to different student needs. Students with these high needs include everything from students with disabilities, English language learners, and students with limited or interrupted formal education (SLIFE), to economically-disadvantaged students or students deemed “high risk.”

All things being equal, WSF is one strategy BPS uses to accommodate the ways in which student need can impact individual school budgets by providing school leaders with the funding they need to best serve their students and meet their unique needs.

The flexible formula that is WSF provides budgetary equity. The BPS budget equation works at its best when the number of students remains constant and predictable.

But what happens when the number of students doesn’t remain constant?

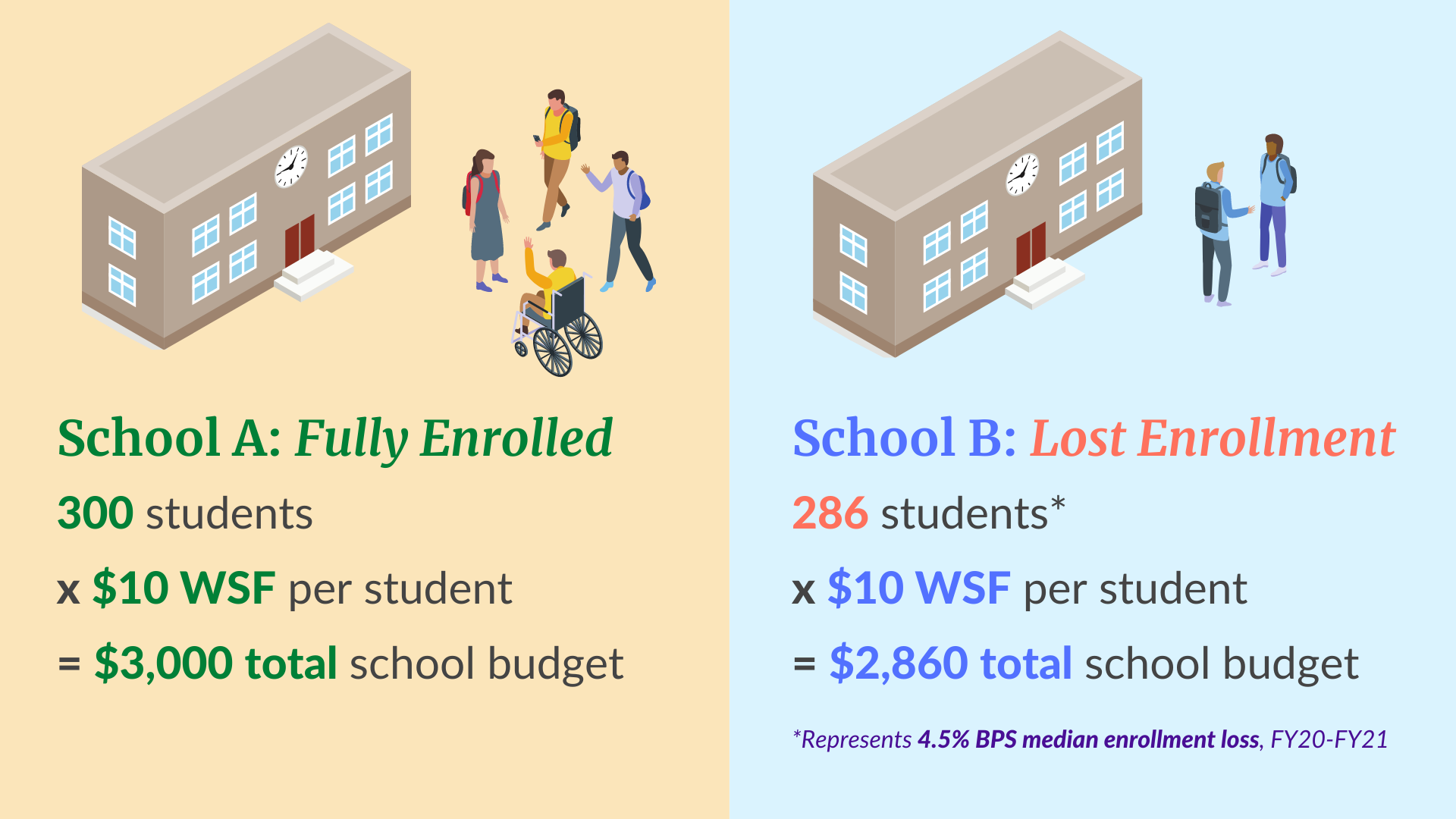

Let’s walk through this answer by comparing two hypothetical school budgets. (A quick note: amounts shown are for illustrative purposes only and do not reflect actual spending or costs.)

School A and School B can each accommodate 300 students. School A is fully enrolled. School B is under-enrolled. Even with equal WSF per student, even a small enrollment decline can create a substantial budget shortfall.

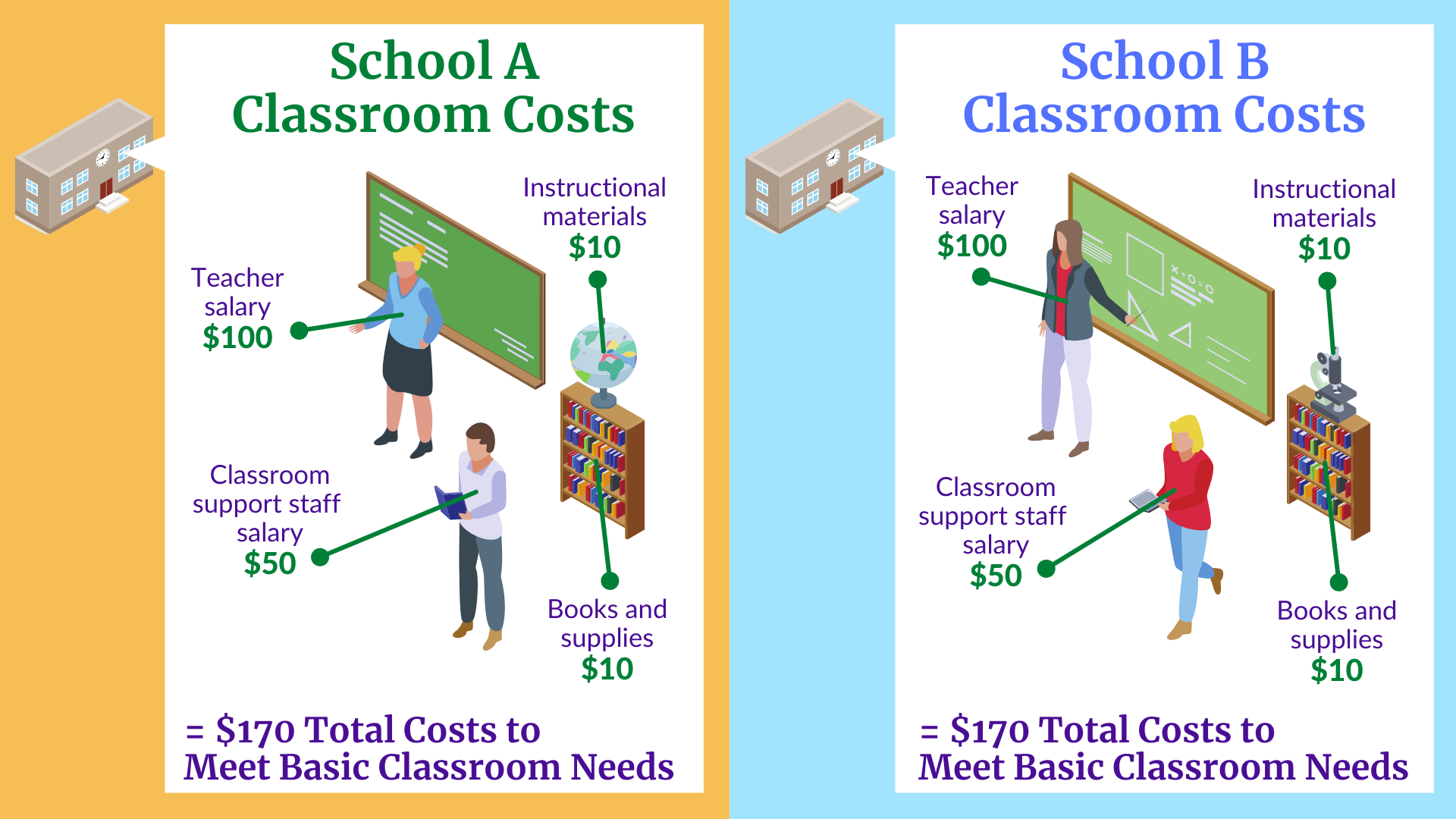

While a 4.5% decrease in enrollment might not seem like much, the ripple effects are felt more acutely within the classroom. All things being equal, classrooms share the same basic needs: teachers, instructional materials, and books. Obviously those needs may look slightly different in implementation, but these basics hold constant despite grade, school, or student population.

As School A’s classroom is fully enrolled, its budget can cover those basic classroom costs. But for School B, even a drop in just 5 students in its classroom has a huge impact on the quality and breadth of services School B can deliver for its students.

Particularly striking is how enrollment can enable discretionary funding at the school level. With a fully enrolled classroom, School A has $30 surplus in discretionary funds that can be used for a variety of “extras,” such as technology, more books, and other enrichments. Meanwhile, School B can’t even meet its most basic classroom needs as a result of enrollment decline.

School B is forced to make difficult tradeoffs to stay within its available budget.

That is of course, unless School B were to receive some kind of additional support.

Soft Landings: A Short-Term Strategy to Close Enrollment Budget Gaps

BPS uses funding colloquially-known as “Soft Landings” to offset budget shortfalls caused by enrollment decline. These fiscal safety nets enable schools to meet their basic needs and costs without having to make sudden, drastic cuts to staff or programs as the result of unexpected enrollment decline.

While Soft Landings may appear to be “extra” money on paper, in practice they are anything but: Soft Landings merely bring under-enrolled schools and classrooms back up to a foundational base to meet those basic classroom needs.

Remember that $30 surplus at School A, a direct result of being fully enrolled? All those “extras” — technology, more books, and other enrichments — are unobtainable to School B even, with the “extra” funds provided in the form of Soft Landings.

Soft Landings counter-intuitively perpetuate a system of Haves and Have-Nots.

Now let’s take it one step further: even though School B has received additional funding to make up for unanticipated enrollment loss, those Soft Landing dollars are actually paying for empty seats.

But that’s just one classroom, you might be saying. Let’s observe what Soft Landings look like when you go up to the school level.

The price of empty seats rises with every empty seat within a school, driving up the total amount of Soft Landings for each school that isn’t fully enrolled.

In our hypothetical example, we’re just looking at two schools. So what happens when you try to implement Soft Landings at scale across an entire school district?

Soft Landings Aren’t Designed to Scale

In FY21 alone, BPS has experienced a median enrollment loss of 4.5%; enrollment is down nearly 9% over the past four years. But once you start working with bigger numbers, it can be hard to comprehend just how big those enrollment losses really are — until you realize that BPS has lost over 5,000 students since 2017.

Those 5,000 students could fill 12.5 schools of average BPS school size.

Using a Soft Landing strategy, every BPS school that experiences enrollment loss receives some kind of supplemental funding — but still doesn’t provide anything extra for students. Soft Landings allow schools to function at their most basic level as a form of short-term stability.

In FY22, 94 out of 121 BPS schools require Soft Landings.

Data source: FY22 Supplemental Funding to Schools via Boston Public SchoolsAnd the price tag for 94 Soft Landings? $33.3 million — or a 633% increase over Soft Landings in FY21. For those keeping score at home: the total BPS budget increased by $36 million for FY22.

By these numbers, Soft Landings — and their implications of paying for empty seats in schools — make up 92% of that increase.

This is the most money BPS has ever spent on Soft Landings in recent memory.

By investing so heavily — and continuously — in Soft Landings, BPS has made a precarious short-term bet that it will see long-term enrollment gains. But declining enrollment trends can’t be ignored.

And even with consistent enrollment over-projection as another budget bandaid, the actual enrollment gains BPS would need to abandon Soft Landings as a fiscal strategy aren’t likely to materialize any time soon to fully recoup its losses.

Soft Landings provide short-term stability at the expense of long-term certainty, but the tradeoff is even bigger than that: as a short-term solution, Soft Landings actually prevent BPS from having more schools like School A: fully-enrolled schools with funding for “extras,” such as additional professional development for teachers, supplemental curricular resources, or new student learning experiences. All of which directly and positively impact student outcomes.

Despite knowing all this, it has become clear Soft Landings have become a fiscal norm within BPS. For how much longer will BPS continue to bolster schools with declining enrollment via Soft Landings?

It begs the followup question: without an influx of new enrollment into Boston’s public schools, where’s the Soft Landing for the entire BPS district?

Final Thoughts

Based on the FY22 budget alone, we can see that over 75% of BPS schools can’t cover the costs to meet their basic needs without substantial fiscal intervention from BPS.

That’s 94 schools out of a district of 121.

Hundreds of classrooms across the city.

Thousands of students — across all grades.

Thinking back to our hypotheticals, we are a district of majority School Bs right now. We know that without Soft Landings, schools would be forced to make cuts that would directly and negatively impact students. It’s a balancing act. It’s about tradeoffs.

But consider the tradeoff BPS has made by choosing to invest in a district of School Bs — and all the lost potential by not investing strategically to become a district of School As. Imagine if BPS had fully-enrolled schools where WSF works at its best, where “extras” — and all of the outcomes associated with them — become the norm.

When we think of student outcomes, graduation data often comes to mind. But a student’s inability to graduate isn’t driven solely by what happens within the span of their senior year: it’s often a compounding of systemic inequities that spans their entire educational career. That compounding of inequities can be traced to what BPS values — for what is a budget, if not a statement of values?

Instead, BPS chooses to invest in a broken status quo — and only just barely breaks even with those investments.

What do these budget numbers reveal about what BPS truly values — and further: why are these values given priority over others?

We hope the next budget hearing can extract some of that rationale.

What’s Next

The next FY22 Budget Hearing will be on Tuesday, Mar. 9 at 5:00 PM Eastern, focused on the Central budget. Zoom webinar, Public Comment sign up, and agenda links will be posted here 48 hours prior to the meeting.

Our next post will examine how money is controlled between school budgets and the Central budget. Make sure you’re following us here on Medium and are subscribed to our Friday newsletters so you don’t miss a post.

You can find our entire Budget Analysis Series, including all reports and slide decks, here at our website.

Questions? Comments? Drop us a line.

About Boston Schools Fund

Founded in 2015, Boston Schools Fund is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that leverages grant-making, strategic partnerships, and data and policy analysis to advance K-12 educational equity in the city of Boston, particularly for those most underserved.