Originally published at HuffPost.

This is my dad: Akira Suwa. It’s rare to capture a photo of him, as he’s typically behind the camera. In 2014, he retired as a senior photojournalist for The Philadelphia Inquirer, his photojournalism career spanning nearly four decades. September 11, 2001 was a Tuesday: My dad’s regular day off. And yet like so many other times in his life, he picked up his camera, got in his car, and headed toward the chaos from which so many other people fled.

I realized I had never really asked my dad what that day was like for him as a photojournalist — I felt it was an important story to tell. In 2010, I spoke with my dad about what his experience was like and what he remembered of that day. This is my dad’s 9/11 story.

PHOTO COURTESY OF AKIRA SUWA

“It was my day off.”

September 11, 2001: My mom, Debbie, had just made coffee and came upstairs. She was sitting on the edge of their bed watching The Today Show when American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower. She shouted for my father, who had just gotten out of the shower: “Akira! A plane just crashed into the World Trade Center! Come look, it’s on TV right now!” He ran into the bedroom with just a towel. My parents watched in horror as United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower — live on television — as millions did that morning.

In his gut, my dad knew it was a terrorist act: over 30 years of journalism experience had taught him that all too well. He threw on a quick change of clothes and was out the door in minutes. He told my mom that he was headed to New York to cover the story. My dad hadn’t even packed a bag — no toothbrush, no medicine, no change of clothes — just his cell phone and a trunk full of cameras and equipment.

“Because I’ve worked so many years for the newspaper, I can judge whether it’s big news or not big news,” my dad told me. “I could tell, as soon as I saw it on TV, this was one of the biggest news stories ever, so I knew I had to cover it. My intuition worked out right away.”

As my dad traveled north on the New Jersey Turnpike, he saw a sea of southbound traffic on the other side of the road as he drove toward New York. He tried in vain to get into the city via the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels, and even the George Washington Bridge — but each had already been closed to traffic. He took some shots along the river by the GWB, then turned around and came home to begin transmitting pictures to his office. He had been home only for a short while when his assigning editor called him, pushing him to go back and try to find a way to get in the city. This time, my dad packed a bag — but he didn’t know when he would be coming back home.

My dad’s memory of exactly how he got into the city was a little fuzzy. He remembers parking his car somewhere in New Jersey and taking a train into downtown Manhattan. He’s not sure if it was the subway or NJ Transit; he just remembers taking one of the few inbound running trains. “I was so lucky I even got into the city,” he told me.

“It was like the moon.”

When my dad came topside, everything was covered in a thick layer of dust and ash. “A couple inches thick,” he said. “It was like the moon, because when you walked, there was dust all over the place. I didn’t have a mask and I tried to avoid [breathing in the dust] as much as I could. I saw cars covered in it — mangled burnt cars. It looked like after a volcano explodes.”

He walked everywhere, walking all the way to Wall Street. It was around 3 p.m. when my dad made it into the city. Most of Ground Zero had been closed off at this point and the press was being kept back at a radius of about six city blocks. Well, most of the press, that is.

“I was treated like an outsider.”

My dad was quick to notice that members of the New York press were given more exclusive access to Ground Zero, such as shooting from the roofs of buildings right next to the site. Other non-New York media outlets couldn’t get that close. “I was treated like an outsider,” he recalls.

When my dad went to Mayor Rudy Guiliani’s press conference that afternoon, he specifically asked if non-New York journalists would be granted close-up access to cover rescue efforts and the damage at Ground Zero. Giuliani’s media camp promised that access would come soon to all journalists, regardless of what outlet they represented. That promise never came to fruition. More frustrating for my father was when he found out that native New Yorker freelancers — who didn’t even have press badges — got exclusive access over photographers from major international outlets. “New York press got special treatment,” my dad said. ”Certain people got certain privileges.”

When interacting with New York officials, my dad encountered roadblock after roadblock. Whether it was NYPD or NYFD, there was no consistent standard of access. It changed minute by minute and from officer to officer. At one point, he tried to take a picture of some firefighters resting. One of the firefighters came over to him and snapped, “Don’t take our picture!” So my dad backed off. “I wasn’t going to get arrested just to try and take pictures,” he told me. “But I felt I was treated in a pretty shoddy way.”

My dad even tried to ask for some help from rescuers when the dust started bothering him. He approached a firefighter he had seen distributing masks to other rescue workers. “I asked him, ‘Do you have an extra mask?’ and he said, ‘No, we don’t have any,’” my dad remembered. My dad watched in disbelief when, moments later, a National Guardsman walked up to the same firefighter and asked for a mask. The Guardsman was handed one without hesitation. My dad was stunned. “I was just doing my job, too.”

A doctor nearby saw the whole exchange and came up to my dad, pulling a mask out of his pocket. The doctor apologized that he had used it, but offered it to my dad all the same. “He gave it to me and I thanked him,” my dad told me. “It was the kindest thing anyone did for me when I was there.”

My dad struggled with how he felt he was treated by city officials and rescuers. “I think there was a racial thing,” he noted. “I’m Oriental [author’s note: English is not my father’s first language]. I’m from a Philly paper.” He said he often got a lot of “what are you doing here?” looks from other journalists and officials.

“I couldn’t even lift my camera.”

Without being able to get close to Ground Zero, my dad focused on the surrounding scenes. “Mostly I photographed people’s reactions, human interest stuff: People looking for lost relatives, makeshift memorials, vigils,” my dad said. “I wanted to get the rescue effort.”

Friends and relatives of victims and the missing would come up to my dad on the street. They’d see his camera and press badge, asking him, “Did you see this person? Do you know what’s going on?” Time after time, my dad didn’t have answers. According to my dad, these people were nice to him and didn’t mind being photographed.

My dad remembers very distinctly interacting with one of these people on the street, even ten years later. “One particular girl was walking by holding a picture — I don’t know if it was her friend or boyfriend. She bumped into me,” my dad recalled. “She asked me if I’d seen this person; she was almost crying. I didn’t know if I had. I was so moved by the way she asked I couldn’t even lift my camera. I completely forgot I had my camera. I felt so bad for her.”

He continued, “After she walked away, I realized I had missed a good opportunity to shoot, so I tried not to involve feeling for my subjects anymore.”

“You become pretty numb.”

My dad stayed in New York for a week covering the aftermath. He was joined by a team of photographers and reporters from The Philadelphia Inquirer. He remembered how hard it was to find lunch: “Everything was closed. You had to go uptown to eat.”

In his career, my dad has seen a lot through the lens: the meltdown at Three Mile Island; on the ground in Iraq and Kuwait during Operation: Desert Storm; spending a month up close with Muammar Gaddafi’s Libyan regime; the fall of the Berlin Wall — 9/11 was no different in the intensity of his assignment.

“I’m glad I contributed to spread this news story for the paper and its readers,” he said to me. But it was hardly a walk in the park and my dad struggled emotionally with covering 9/11. “I felt so bad about what was going on,” he said. “You see this kind of stuff, seen tragedy in my career, and you become pretty numb. It’s not good, but it’s the nature of the business. I felt bad about so many people dying.”

My dad didn’t have the luxury of dwelling on the emotional impact of what had just happened to our country, to these individual people and lives. “Otherwise I can’t take pictures,” he said. He would return to his hotel every night, often depressed and doubting if he should have taken the assignment in the first place. “Maybe I’m too cold, but I have to be,” my dad said. ”If I start thinking about any kind of tragedy, I just can’t cover it.”

After a moment, he continued: “Sometimes it affects me later on.”

Lasting Images

My dad never got close to Ground Zero. The closest he ever came was about 2 blocks away, before officials shooed him away again. He only ever spent about 3 to 4 hours a day focused on trying to get shots near Ground Zero, usually at a distance of about 4 to 5 blocks away. “As soon as I got back to the hotel every night, I got into the shower and washed everything,” he says. In retrospect, he’s glad he didn’t spend so much time at Ground Zero because thankfully, he hasn’t developed the health problems that many of the first responders have in the decade since. “Maybe that was one of the good things that happened to me,” he thinks. Still, my dad is registered on the World Trade Center Health Registry just to be safe.

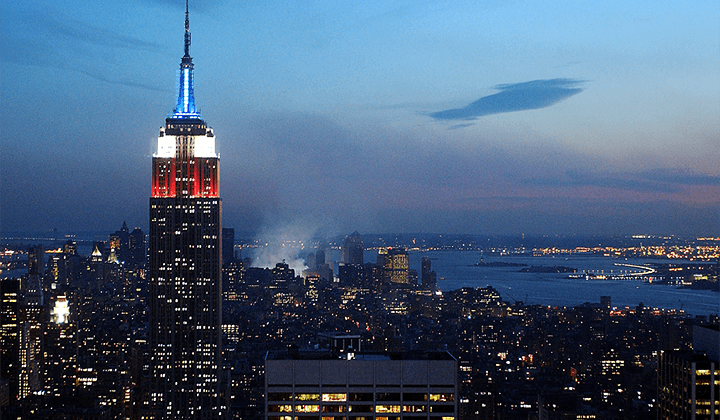

For as much as my dad wanted to get shots close to Ground Zero, he had to get creative. He decided to try and get some shots from higher ground. On September 13, he came up with an idea. He went to Rockefeller Center up to the 65th floor to the Rainbow Room restaurant.

“I spoke to the manager and asked if I could shoot at dusk from their windows, so I could get the Empire State Building — now lit up in red, white, and blue lights — while Ground Zero could be seen smoldering in the background,” he told me. The manager agreed and about two hours later, my dad came back, camera in hand. He got his only shot of Ground Zero. It’s haunting photo of a new New York skyline at dusk, the sky unmarred by airline contrails as all planes were grounded. Of all the thousands of images he took that week, this one image was my dad’s favorite photograph:

PHOTO COURTESY OF AKIRA SUWA

It was never published.